Introduction

Before John Barry was asked to score for Dances with Wolves (1990), an epic western film directed by Kevin Costner, he had been artistically criticised by some people for being a one-theme-per-film composer, repeating musical motifs ad nauseum in his compositions and as a result, his scores had begun to sound very alike in structure and instrumentation (Filmtracks – “Dances with Wolves”, 2016). Dances with Wolves is the definitive rebuttal of such allegations. Barry multi-layered the score with at least eight different themes and developed them with technical agility. The two-minute cue for the scene “The Death of Timmons” is a great reflection of how, as a composer of the Silver Age of film music history, Barry smoothly combines two themes that are in distinctly different styles: “the Pawnee theme” and “the John Dunbar theme”, and successfully unifies the score.

The Composer – John Barry

Like the other composers of the Silver Age (1950s–mid-1970s) of the film music history, Englishman John Barry was invested in classical music but was also renowned for his skill in other genres, such as jazz, pop/rock and R&B. Bon in York, England, on November 3, 1933, he grew up as a talented pianist and trumpet player. Later, he took a jazz course with jazz composer Bill Russo and worked as an arranger for an orchestra. He first gained fame as the leader of the band “The John Barry Seven” that he founded in 1957. In 1962, he was approached to arrange Monty Norman’s James Bond theme song, which prompted him to write scores for the next 11 films in the series (Famous Composers: John Barry, 2020).

Barry was nominated for several awards and received many trophies for his work: five Academy Awards, one Golden Globe Award and two BAFTA Awards for several of his works, such as Born Free (1966), Out of Africa (1986) and Dancing with Wolves (1990) (Wikipedia: John Barry Composer, 2020). He died in New York on January 30, 2011 and is respected even now for his skills as a talented and creative composer who has made an indelible impact on the film music world.

The Film – Dances with Wolves by Kevin Costner

The film is a large-scale canvas drama set towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant John Dunbar is seriously injured and branded a hero after unintentionally driving Union forces to triumph. He is granted leave to apply for any task that he prefers. He selects a post in the isolated Dakota Territory, deep in the heart of the Sioux country, so that he can “see the frontier until it’s gone,” implying the expansionist powers of Western culture. While at his isolated base, he encounters and ultimately gains the trust of the local Sioux tribe, shedding his preconceptions of them as barbaric savages, instead, he is drawn to their family-oriented lifestyle and love for nature.

He then leaves the fort, settles in with the group and marries Stands with a Fist, a white woman whose family had been murdered by the Pawnee tribe and grew up in the Sioux community, Dunbar is seized by the Western army when he returns to the fort to collect his journal. Tried and sentenced as a traitor, he is sent back to be executed. However, his Sioux friends attacked the group, the soldiers were killed, and Dunbar was saved. He reaches Sioux’s camp, but soon decides to leave because he knows that the army will unceasingly search for him, putting the tribe at risk. Thirteen years later, Sioux’s homes are burned, their buffalo is gone, and the last free Sioux tribe is turned over to the White Authority at Fort Robinson, Nebraska.

The Scene – “The Death of Timmons”

The scene in which Pawnee kills Timmons starts at about 36:22 in the film. Before this scene sets in, Dunbar is offered a ride to the fort with Timmons, a mule wagon provisioner. Timmons leaves as Dunbar decides to stay at the fort alone. A band of Pawnee men stare at a line of smoke in their territory. The leader decided to attack and kill the “white men” who, ignorantly, had an open fire on their land.

The scene starts with a close-up of Timmons making food on the journey back to Ft. Hays. Suddenly, an arrow is unexceptedly shot at Timmons’ back. As he looks back, he notices that a Pawnee man is coming after him. The cue begins as he gets up to run away from the Pawnee. Unfortunately, he is severely injured by the subsequent arrows shot in his body. As the Pawnee takes his wagon, he murmurs, “Don’t hurt my mule.” Timmons is then scalped, murdered in a most violent and cruel way.

Analysis of the Cue in the Scene

John Barry was one of the Silver Age composers that were active in keeping alive the traditional orchestral vocabulary while experimenting and embracing other musical elements (Davis, 2010, p.43). This is evident in the cue for the scene “The Death of Timmons”, which consists of two themes with distinctive characters: “the Pawnee theme” and “the John Dunbar theme”. The cue first starts with “the Pawnee theme”, followed by “the John Dunbar theme”. It concludes with a fanfare variation of “the Pawnee theme”.

This section will first analyse the musical elements in the two themes in the context of the film music style. It will then discuss how Barry carefully interweaves these different thematic moments in this cue with his brilliant usage of instrumentation to unify the score.

The Pawnee Theme

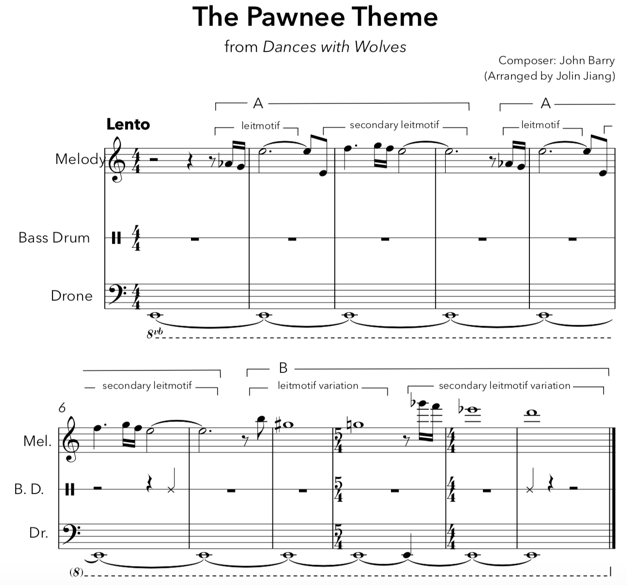

In contrast with the Sioux tribe, the Pawnee tribe represents the “evil” Indians of the film. John Barry assigns them with an angular, sinister theme – probably the most unique of the film (see Figure 1).

“The Pawnee theme” is made up of two leitmotifs and their variations. Both leitmotifs contain the rhythmic pattern of two semiquavers followed by a long note to create a sense of uneasiness and urgency. The A section is repeated and is then followed by a B section, which essentially is comprised of the variations of the leitmotifs in a higher register to exaggerate the tension created by the Pawnee tribe. For example, the “leitmotif variation” B5-G#5-G5 pattern is a modified retrograde inversion form of the original leitmotif. The result of this technique is a consistently disturbing chromatic melody.

Interestingly, there is no harmony in the theme. The single-lined melody is only accompanied by tumultuous bass drum effects, and a threatening bass pedal drone (at around E1) that rumbles in the background. The notes in the melody clashes with the drone note but not clashing within a chord.

Unlike composers from the Golden Age that embraced lush Romantic orchestral scores, John Barry used these contemporary sounds and textures influenced by Bartók, Schoenberg, and other 20th century composers here (Davis, 2010, p.36). This dissonant and atonal sound is extremely effective for depicting the violent, nasty Pawnee tribe.

The John Dunbar Theme

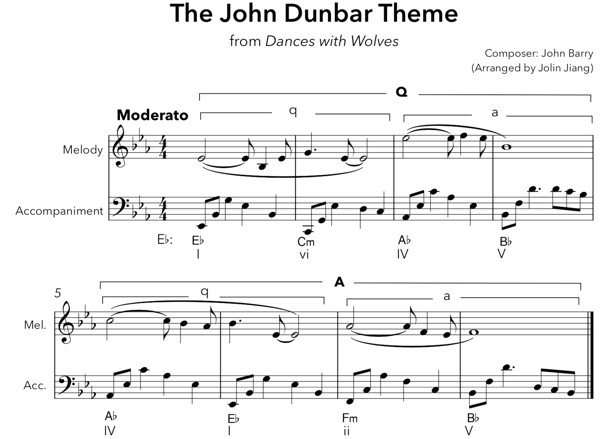

“The John Dunbar Theme” is a typical fantasy romantic song, where a lush symphony orchestra performs a sentimental, expansive melody. The warm and hopeful piece portrays the protagonist John Dunbar’s character perfectly: positive, wholesome, loving, yet a little melancholy. Like many other theme scores by composers of the Silver Age, such as the Main Titles from Breakfast At Tiffany, “the John Dunbar theme” has a “pop” twist to it.

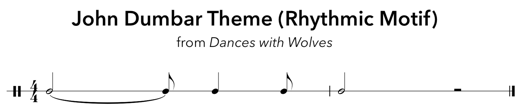

The entire theme is based on one simple rhythmic motif with a noticeable syncopation pattern (see Figure 2).

The classic 8-bar theme consists of four of this rhythmic motif in different melodic contours, which form two mini, and one major “question and answer” phrases. This syncopation, when combined with the simple accompaniment, create a polyrhythm (see Figure 3), a stylistic trait of pop music (New World Encyclopedia: Pop music, 2012).

The composer’s pop origin can also be seen in the simple, affectionate and romantic orchestration, where the lower half of the orchestra plays the harmony and the upper half plays the melody. The accompanying instruments outline the simple I-vi-IV-V chord progression with an expansive I-V-III pattern which provides a romantic pop style. For example, the first three notes used in the accompaniment for the first bar are Eb, Bb and G, which correspond to the tonic (I) note, the dominant (V) and the mediant (iii) notes of the Eb major chord.

A Unified Cue

As discussed above, the two themes used in this cue are of different styles. A variety of gestural and textural techniques are used to unify the distinct musical materials and make the transformations as seamless as possible. The first structural device is the use of a common tonality. The Pawnee theme in the opening of the cue as they approach Timmons on the scene is written in E minor. As Timmons asks the Pawnee not to hurt his mules, his character is redeemed, and granted the privilege of the John Dunbar theme. This major key pastoral interlude is then manipulated and played in E major here rather than its customary E flat major. The cue is then reasserted in E minor as the Pawnee murders Timmons and leaves the scene.

Secondly, Barry used the same instruments to codify the emotional palette throughout this cue. The cue opens with an ominous bass pedal swell in the Pawnee theme. A warm solo flute plays the first one or two notes in the motif, it is soon punctuated by a solo flutter tongue trumpet. The melodic line is then handed over to high strings playing in unison. This angular theme is therefore shared by fragments on the flute, trumpet and strings which are also closely linked to the instruments used in the John Dunbar theme that follows. When the audience first hears it in the film, the John Dunbar theme opens with a noble, Coplandesque, solo trumpet, associating with the character’s romantic and lonely nature. When the theme is used in this cue to represent Timmons’ death and redemption, the usual warm and mellow solo trumpet sound is replaced by a soft and quiet solo flute, where the strings play the accompaniment. The cue then quickly turned sour as the Pawnee scalped him.

The deep bass drum booms that represent the Pawnee’s violent and threatening nature are played eleven times throughout the cue: in the Pawnee’s theme, at the end of the John Dunbar’s theme and as the Pawnee leave. As the Pawnee ride off, the booming of the bass drum echoes over the ominous pedal note, soft but threatening (Brownrigg, 2003, p.83). This is also excellent evidence of how Barry consolidates the cue, where the themes are playing off each other to expert effect (Boxton, Movie Music UK, 2008).

Conclusion

John Barry’s score for Dancing with Wolves is arguably his magnum opus, with the scope and elegance of an exquisite drawing. Although the dominant style tended to be Romantic orchestral music, aspects of atonal works and pop music were also present. The study of the cue for the scene “The Death of Timmons” showed the extent of the hybridity of the score, a common style of scores during the Silver Age. By skilfully taking thematic materials from different sound worlds and blending them, Barry was able to present a unified masterpiece with a beautifully crafted emotional palette in the context of the film.

References:

Brownrigg, M. (2003). Film Music and Film Genre (a thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy). Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/40108516.pdf

Broxton, Jonathan (2008). Movie Music UK: Dances with Wolves – John Barry. Retrieved from https://moviemusicuk.us/2008/11/06/dances-with-wolves-john-barry/

Davis, R. (2010). Complete guide to film scoring: The art and business of writing music for movies and TV. Boston: Berklee Press.

Famous Compsoers: John Barry (2020). Retrieved from https://www.famouscomposers.net/john-barry

Filmtracks – Dances with Wolves (2016). Retrieved from https://www.filmtracks.com/titles/dances_wolves.html

New World Encyclopedia: Pop music (2012). Retrieved from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Pop_music

Wikipedia: John Barry (composer) (2020). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Barry_(composer)